When we measure a length, with a ruler, say, we can’t measure it exactly. The ruler will be marked off in, say, millimetres, and the length we are measuring will probably fall somewhere between two markings on the ruler, so we can only say that the length is somewhere between the distance between the two markings and the start of the ruler.

Probably. Actually there are a number of things that could mess up our measurement. We may not be able to line up the start of the length we are measuring with the start marking on the ruler, as the marking on the ruler is not of zero width. The best we can do, when aligning one end of the length to be measured with the ruler, is to align the start of the length to the middle of the marking on the ruler.

We then have to transfer our attention to the other end of the ruler. Probably the other end of the length and the edge of the ruler don’t align, so we shuffle the ruler to try to align the two ends of the length with the edge of the ruler, checking all the time that the start of the ruler is in line with the start of the length to be measured.

When all is aligned we can then read of the approximate value of the length, assuming that the ruler is still properly aligned and that the start of the ruler is still properly aligned with the start of the length. However, as mentioned above the end of the distance being measured will probably fall between two markings.

So any measurement with the ruler should be stated with an estimate of the margin of error in the answer. “About 73mm, with an error of about 0.5mm” might be a reasonable estimate.

The accuracy of a measurement may depend on the material from which the ruler is made. It may be wood, plastic or metal, or some other material. Wood is a natural material, and as such it may warp, or shrink or expand unevenly. It may deteriorate over time, so that today’s measurement may be slightly different from today’s. The ink used to make the markings may migrate into the wood through natural pores and cracks in the wood, rendering them wider and fuzzier than when the ruler is new.

A metal ruler can be marked more accurately, and the markings won’t blur, and the markings can be much thinner or sharper than those of a wooden ruler. Unfortunately metal will expand and contract depending on the temperature, adding errors to the measurements. This can be alleviated by careful choice of alloy for the ruler, but not eliminated.

All rulers are these days fabricated by machines of course, and the markings are made by these machines. Such a machine has to be as accurate or more accurate than the end product of course, which means that the scale marks must be located more accurately, and probably be narrower than those of the end product.

In order to be more accurate, various techniques are used to achieve the extra accuracy, and I’m not going to discuss them here, mainly because I can only guess what they are! Vernier scales and error averaging techniques spring to mind, but as I said, I don’t what is actually used.

Microscopes and similar allow the measurement of very small distances against a scale calibrated to very small tolerances. This pattern is repeated endlessly – to measure small distances accurately your measuring device (or technique) needs to be an order of magnitude more accurate than the distance to be measured.

If we want to measure atoms, we need an atomic sized scale and that cannot be made of atoms, obviously. We can use electromagnetic waves, other atoms, subatomic particles and so on, of course, but we are now in the quantum world, so not only do we have the sorts of issues mentioned above, but we have issues that related primarily to the quantum world – such as the Uncertainty Principle, and the fact that an atom can behave like a particle or a wave.

Down at these levels we use atoms to measure other atoms – there is of course no possibility of a ruler type scale which is made up of atoms. Instead things are measured by noting the frequency of emissions from the atom as its electrons changes from one quantum state to another.

This is referred to as a quantum jump and is popularly interpreted as an electron moving from one electron shell to another, in the common view of an electron orbit around the nucleus of an atom like a planet around a star.

A popular view is that at quantum levels the apparent continuity in time and space is not seen and that space and time appear to have a discrete structure. At some scale this makes it impossible to measure very small lengths, as it is impossible to tell whether or not two points are at different locations or not.

It follows that in the usual macro world that apparent continuity is probably illusory – if we can’t tell the difference between two points at a very small level, our measurements at the macro level are not well defined. It seems that the appearance of continuity at the macro level is an emergent phenomenon.

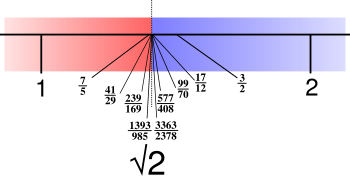

Maybe. The appearance of continuity probably comes from the fact that when we look at a line from A to B we can always pick a point C between them. We can then pick a point D between A and C and a point E between A and D and so on, apparently forever. But in fact the process has to stop, and the stopping point is where we find that we can’t distinguish the two end points of the line.

Is the issue caused by a conflict between our physics, which is at heart a description of the world as we see it, and what the world is actually like? A line is a mathematical concept which has extent (length), but no width. In the real world a line is marked by some means, pencil or laser beam, and has an extent, which is what we are trying to measure, and certainly has some width, the width of the lead of the pencil, the width of the laser beam. Are we starting to find out about the things that we can’t know about the world?