A cursory search on the Internet doesn’t tell me one way or another if Erwin Schrodinger owned a cat. Nevertheless he could have owned a cat, so the existence of Schrodinger’s actual cat is unknown to me. David Deutsch might possible argue that Schrodinger’s decision to own a cat or not own a cat resulted in two parallel worlds.

The above is obviously a play on the original scenario outlined by Schrodinger, the famous Schrodinger’s Cat thought experiment. The cat’s state before the box is opened is a strange state, referred to as a superposition, where the cat is both alive and dead. When the box is opened it is argued that this state is somehow resolved with cat being definitely alive or dead.

Suppose that we install a detector in the box with the cat which determines whether or not the cat is dead and notes the time when it dies. Does this resolve the paradox? After all, if the detector says that the cat died three minutes ago, then we now know exactly when the cat died.

This doesn’t resolve the issue, though, as the detector will also be in a superposition until the box is opened – we don’t know if it has been triggered or not. Of course, some people, including Schrodinger himself, are not happy with this interpretation, and it does seem that, pragmatically, the cat is alive until the device in the box is triggered and is thereafter dead.

However the equation derived by Schrodinger appears to say that the cat exists in both states, so it appears as if Schodinger’s “ridiculous case” (his words) is in fact the case. Somehow the cat does appear to be in the strage state of superposition.

If we look at the experimenter, he (or she) has no clue before opening the box whether the cat is dead or not. Nothing appears to change for him (or her), but in fact it does. He (or she) is unaware of the state of the cat, so he (or she) is in the superimposed state : He (or she) is unaware whether or not the cat is alive or whether it is dead, which is a superposition state.

Yet we don’t find this strange. If we remove the scientific gadgets from the box, this doesn’t really change anything – the cat may drop dead from old ages or disease before the box is open. Once again we cannot know the live/dead status of the cat until we open the box.

So, what is special about opening the box? Well, the “when” is very important if we consider the usual case with the scientific gadgets in the box. If we open the box early we are more likely to find the cat alive. If we open it later it is more likely that the cat will be dead. Extinct. Shuffled the mortal coil.

So it is the probability of atomic decay leading to the cat’s death that is changing. It may be 70% likely that cat is dead, so if we could repeat the experiment 1000s of times 7/10th of the time the cat is dead, and 3/10th of the time the cat is still alive. Yeah, cat!! (There’s also a possibility that the experimenter gets a whiff of cyanide and dies, but let’s ignore that.)

But after the box is opened, the cat is 100% alive or 100% dead. Apparently. How did that happen? Some people claim that something mysterious called “the collapse of the waveform” happened. I don’t think that really explains anything.

The same thing happens in the real world. If I don’t check my lotto tickets I’m in a superposition state of having won a fortune and not having won a fortune. When I check them I find I haven’t won anything. Again! I must stop buying them. They are a waste of money.

The many worlds hypothesis gets around this by postulating the splitting of the world into two worlds whenever a situation like this arises. After I check my lotto ticket there are two worlds, one where I am a winner and one where I am not. How can I move to the world where I’m a millionaire? It doesn’t seem fair that I stuck here with two worthless bits of paper. does it?

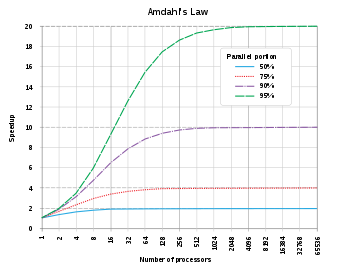

And what does the probability mean? In the lotto case it is 1 in an astronomical number that I come out a winner and almost 1 that I get nothing. In the cat case it may be 60/40 or 70/30, and in the cat case it changes over time.

If the world splits every time a probabilistic situation arises, then the probabilities don’t actually mean much. What difference does it make if a situation is “more probable” than another situation if both situations come about in the multiverse regardless? It doesn’t seem that it is a meaningful attribute of the branches. What does it mean, in this model that branch A is three times more likely than branch B? Somehow a continuum (probability) reduces to a binary choice (A or B).

We could consider that the split is not a split at all, but that reality, the universe, whatever, has another dimension, that of probability. Imagine your worldline, a worm travelling through the dimensions of space and the new one of probability. You open the box and lo! Your worldline continues, and the cat is now dead or alive, but not both.

But which way does it go? That is determined purely by the probabilities, by the throw of the cosmic dice, but once it chooses a path, then there is no other possibility. In the space dimensions you can only be in one place at a time. If you are at A you cannot be at B, and similarly in the probability dimension, if you are at P you cannot be at Q.

However any point P (the cat is still alive!) is merely a point on the probability line. There are an uncountable number of points where the cat is alive and also an uncountable number of points where the cat is deceased. But the ratio between the two parts of the line is the probability of the cat’s survival.